The Devil in Gay, Inc.

How the Gay Establishment Ignored a Sex Panic Fueled by Homophobia

While striving to enhance penalties for homophobic thought-crimes, the gay mainstream has been tossing people harmed by some of the worst excesses of homophobia overboard. In the 1980s and ’90s, a wave of baroque child-molestation trials steeped in bias against sexual minorities swept the U.S. In response, LGBTQ organizations sometimes joined in virtual lynchings. More often, they maintained a silence interrupted only by the mantra, “We are not child molesters.”

Scores of day-care workers, nursery school teachers, baby-sitters and others imprisoned on false sex-abuse charges during the height of the child-protection panic have been exonerated and freed, but a number of almost certainly innocent people convicted of sex crimes against children remain under lock and key. Among them are four women from San Antonio, Texas, now in their second decade of incarceration.

The women’s ordeal began in September, 1994, when Serafina Limon caught her granddaughters, Stephanie and Vanessa, in apparently sexualized play with naked Barbie dolls. When Serafina reported this scene to her son Javier, the girls’ father, he concluded the girls, aged seven and nine, had been exposed to lesbian sex at the home of their aunt. Police were informed. The girls were brought to the Alamo Children’s Advocacy Center for evaluation. Following an investigation, Javier’s estranged wife’s younger sister, Elizabeth Ramirez, 19, and three of her friends were charged with multiple counts of aggravated sexual assault.

In July, Liz Ramirez’s nieces had spent a week at her San Antonio apartment. During that period, a Latina lesbian couple, Anna Vasquez and Cassandra “Cassie” Rivera, had visited, bringing with them Cassie’s children. Liz’s roommate, Kristie Mayhugh, was also present. Neighbors’ children ran in and out of the apartment. Days passed without incident. When the girls returned home, they showed no signs of trauma.

The chief investigator was a homicide detective, Thomas Matjeka, who had never previously interviewed children thought to have been sexually abused. He made no recordings of his sessions with Stephanie and Vanessa, who had already been grilled by others including their father. Interrogating Liz Ramirez, Matjeka told her that although she currently had a boyfriend, he knew about her sexual history of involvement with women, implying that homosexuality made her a menace to children.

The case took a long time to go to trial. Elizabeth Ramirez was tried separately and convicted in February, 1997. Having previously been offered ten years’ probation in exchange for a guilty plea, she received a prison term of 37 years and six months. A year later, Anna, Cassie, and Kristie were tried together, found guilty, and given 15-year sentences. At both trials, prosecutors repeatedly alluded to the defendants’ sexual orientation, implying it was a short step from lesbianism to child rape. There was minimal evidence except the uncorroborated testimony of Liz Ramirez’s nieces, who recited carefully prepped claims that the women had pinned them down and inserted objects and substances including a tampon and a strange white powder into their vaginas.

The women, who have come to be known as the “San Antonio Four” or the “Texas Four,” have gained a growing number of supporters convinced they are innocent. Few of those advocates belong to the gay community of San Antonio, a city that ironically, according to the 2010 U.S. census, has the highest concentration in the U.S. of lesbian parents raising children under 18.

In scores of trumped-up cases dating back to the early ’80s, police claimed to have apprehended groups of care-givers conspiring to have sex with children entrusted to their care. The abuse scenarios, often confabulated through coercive questioning of child witnesses, were given a diabolical spin. Investigative journalist Debbie Nathan, co-author of Satan’s Silence: Ritual Abuse and the Making of a Modern American Witch Hunt, has called the San Antonio Four debacle “probably the last gasp of the Satanic ritual abuse panic.”

Somewhere in the long, rich pageant of American brutality, there may indeed have been instances of devil-worshippers sexually abusing children. But the Satanic ritual abuse (SRA) pandemic was made of thin air. Rigorous investigations, some by law enforcement officials eager to unearth a vast Satanic underground, have shown that no such network exists. As historian Philip Jenkins states in Moral Panic: Changing Concepts of the Child Molester in Modern America, “The SRA movement represents an eerily postmodern dominance of created illusion over supposedly objective reality—what Baudrillard would term the stage of pure simulation.” [P. 177.]

The nonexistence of SRA in the real world didn’t prevent it from becoming a staple of junk journalism and daytime talk shows. The implausibilities of self-proclaimed SRA survivors’ narratives didn’t lessen the fervor with which belief in SRA was promoted by such “experts” as New York psychiatrist Judianne Densen-Gerber, founder of the Odyssey House drug-rehabilitation chain, and such public personalities as Geraldo Rivera, Oprah Winfrey, and Gloria Steinem. “Believe It!” trumpeted Ms. magazine. “Cult Ritual Abuse Exists!”

The phenomenon owed a great deal to the 1980 publication of Michelle Remembers, in which Michelle Smith, a patient of Canadian psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder, described how she had, through treatment, overcome traumatic amnesia to access awareness of childhood abuse by the ubiquitous, powerful “Church of Satan.” Michelle remembered being raped, locked in a cage, forced to witness human sacrifice, and smeared with fresh blood.

The book was a bestseller. Eventually exposed as fraudulent, Michelle Remembers followed such ’70s pulp-psych blockbusters as the multiple personality/recovered memory saga Sybil into popular consciousness. The pseudo-memoir validated rumors that thousands of cultists were subjecting thousands of children to outré sexual assault. Both the Smith/Pazder book and Sybil helped popularize the idea that although countless people had, as children, been subjected to ritualistic kinky sex, most required therapeutic intervention to recall such horrors. That notion gave rise to a huge, lucrative, now compellingly debunked therapy movement centered on repressed memory.

SRA allegations were excluded from evidence presented to both juries at the trials of the San Antonio Four, but belief in that phenomenon shaped pre-trial investigations. Examining pediatrician Nancy Kellogg, respected co-founder of the Alamo Children’s Advocacy Center, was a true believer in SRA. In her medical reports on Stephanie and Vanessa, Kellogg stated that she had notified the police that the abuse, which she was convinced took place, might well have been “Satanic-related.”

The principal mass sex-abuse scares of the SRA era involved “sex rings” and imagined predation at child-care facilities. Many of the alleged abusers were said to be manufacturing child pornography, although no child porn linked to SRA cases was ever found and used as evidence. Most of the sex-abuse trials flouted standards requiring presumption of innocence and determination of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

In Sex Panic and the Punitive State (2011), Roger N. Lancaster asks, “[D]o overblown fears of pedophile predators represent new ways of conjuring up and institutionally using homophobia, even while disavowing it as motive?” [P. 17.] Typically, late 20th-century witch hunts began with allegations tinged with homophobia even when the principals were straight. A man, perceived as gay, with children directly in his care—or working in close proximity to children—would be suspected of having preyed upon at least one boy. There was a widespread assumption that any man who sought work with very young children must be gay.

The panic was launched in 1982 when a volley of accusations echoed through Kern County, California, where fabricated evidence pointed to half a dozen active sex rings in and around the city of Bakersfield. Thirty-six people were arrested and convicted of child rape. One of the harshest sentences, 40 years, went to gas plant foreman John Stoll, convicted of 17 counts of molesting five boys.

In 1983, as the Bakersfield sex-abuse frenzy wore on, the hysteria spread southeast to the L.A. suburb of Manhattan Beach, site of the McMartin Pre-School. The McMartin case, which morphed into the longest, costliest criminal process in U.S. history—a marathon ending in no convictions—started with a schizophrenic’s fantasy that Ray Buckey, the founder’s grandson, had sodomized her two-and-a-half-year-old son. Seven McMartin employees were implicated in a host of imaginary crimes including kiddie-porn photo shoots and dark, perverted rites in nonexistent tunnels. Michelle Smith and Lawrence Pazder appeared on the scene to advise prosecutors and comfort parents.

Lurid publicity sparked fresh accusations. In late September, 1983, about three weeks after the McMartin case began to snowball, authorities in Jordan, Minnesota, began delving into allegations that 24 adults and one teenager held orgies involving over 30 children, including infants. By 1984, the contagion had reached Massachusetts. Gerald Amirault, whose mother ran the Fells Acres Day Care Center near Boston, was accused of raping a four-year-old boy; he and his mother and sister were imprisoned for a host of crimes against children, including production of never-located child pornography. As the Amirault investigation came to a boil, a 19-year-old gay child care worker, Bernard Baran, was arrested in Pittsfield at the opposite end of the state.

The child-molestation panic that spread across the U.S. in the 1980s had gay-specific antecedents. These included two high-profile witch hunts targeting largely imaginary cabals of gay men. One tore through Boise, Idaho, in 1955; the other hit the Boston area in 1977-’78.

In Boston, anti-gay dread was incited and amplified by Christian citrus-industry shill Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, a Florida-based propaganda blitz against gay rights ordinances. Bryant’s chief message was that gay men and lesbians target children for conversion to the “homosexual lifestyle.” As John Mitzel notes in The Boston Sex Scandal (1980), the Save-Our-Children panic was given respectable secular underpinnings by Dr. Judianne Densen-Gerber of Odyssey House, who proclaimed that child pornography was rampant and mainly the work of rapacious queers. In California, meanwhile, State Senator John Briggs railed against gay teachers, accusing them of “seducing young boys in toilets.”

At the heart of the Massachusetts furor was a man in Revere, a Boston suburb, who had been letting friends and acquaintances use his apartment as a discreet place to bring male hustlers for sex. Suffolk County’s paleo-Catholic District Attorney, Garrett Byrne, 80, learned of the arrangement and ordered a crackdown. Local rent boys were rounded up and ordered to name their johns. Thirteen cooperated. Little more than the depositions of two fifteen-year-old hustlers were finally used to indict two dozen men for over 100 sexual felonies. The lives of the accused adults were shattered, although only one—Dr. Donald Allen—went to trial. Allen received five years’ probation; only the man who supplied the apartment did prison time. Most of the streetwise young men corralled by Garrett Byrne were above the state’s legal age of consent, 16, though at a time when sodomy laws could be enforced at the whim of the enforcer, age of consent was almost beside the point.

The scandal owed much of its heat to the input of Boston-based pediatric nurse Ann Burgess, who created a diagnostic sex-ring model widely applied in the ’80s and ’90s, from the Bakersfield circus to the 1994-’95 panic in Wenatchee, Washington, where 43 adults, including parents and Sunday school teachers, were held on 29,726 false charges of sexual abuse. Burgess asserted that international gay sex rings were flying boys to secret locations where they could be ravished. Although most of the child-protection books she wrote or edited, such as Child Pornography and Sex Rings (1984) and Children Traumatized in Sex Rings (1988), have dated badly, Burgess now teaches victimology and forensics at Jesuit-run Boston College. She remains influential. One of her pupils, Susan Kelley, played a key role in the Amirault case, interviewing children by means of leading questions and “anatomically correct” dolls, refusing to take no for an answer.

Fighting back in 1978, Boston activists formed the Boston/Boise Committee, out of which grew two organizations that survive. One was the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), originally focused on relationships between adult men and adolescents, now demonized out of all proportion to the varied predilections of its minuscule membership. The other was Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD, not to be confused with the anti-defamation group GLAAD). Created as a legal resource for gay people accused of sex crimes, GLAD long ago ceased to deal with criminal cases, choosing instead to work usefully on HIV/AIDS and gender identity issues, and less usefully on marriage rights and hate-crime legislation.

No gay organization of any kind acknowledged the existence of Bernard Baran. The first day-care worker to be convicted of mass molestation, Baran went to trial before the McMartin staff and the Amirault family. He was an openly gay teacher’s aide at the Early Childhood Development Center (ECDC) in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. His original accuser was a woman who had just removed her four-year-old son from ECDC, complaining about the facility’s willingness to let a homosexual work with children. The woman and her boyfriend had a history of violence and substance abuse. The investigation, however, yielded tidier accusers. The case took on a measure of gravitas when a middle-class mother who taught ceramics at Pittsfield’s posh Miss Hall’s School for Girls claimed Baran had attacked her three-year-old daughter.

A grand jury was shown edited videotapes of child interviews, omitting extensive footage showing the children being coached, prodded, and offered rewards while they denied everything. Baran’s attorney, hired out of the phone book on a $500 retainer, did not object. By the time Baran’s trial began in January, 1985, he had been indicted on five counts of rape and five counts of indecent assault and battery against two boys and three girls aged three to five. A third boy was added at trial. The courtroom was closed for children’s testimony which, when not incoherent, echoed prompting from prosecutor Daniel Ford. Ironically, the “index child”— Paul Heath, 4, the boy whose mother made the first accusation—was dropped from the case after when he refused to cooperate in court, denying abuse and responding to questions with “Fuck you!”

The prosecution exploited jurors’ fears of homosexuality. At a time when the specter of AIDS was everywhere, the Berkshire County D.A. adopted a diseased-pariah strategy. Because Paul Heath had tested positive for gonorrhea—according to a test now known to produce a high rate of false positives—Ford brought in a physician to testify to the prevalence of gonorrhea among prostitutes and homosexuals. It didn’t matter that Baran’s gonorrhea tests came back negative. Paul Heath had, in fact, recently made a more credible disclosure of abuse by one of his mother’s boyfriends, a likelier source of STD. Word that this allegation was being investigated never reached Baran’s lawyer.

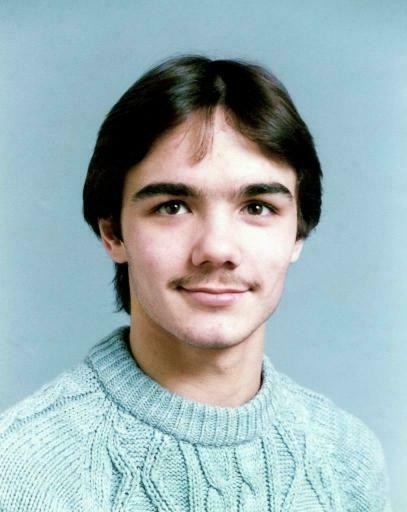

In his closing argument, Ford described Baran’s “primitive urge to satisfy his sexual appetite.” Given access to children, he continued, Baran acted “like a chocoholic in a candy factory.” Found guilty on all counts, Baran received three concurrent life sentences. Sent to the maximum-security state prison at Cedar Junction, he was savagely raped on arrival. He had repeatedly been offered—and refused—five years of low-security incarceration in exchange for a guilty plea.

Similar cases with homophobic overtones kept finding their way into court. Prosecution of lesbians for ritualistic sex abuse was rare, but hardly unknown before the arrest of the San Antonio Four. Women enmeshed in sex-ring hysteria were often accused of assaulting young girls. At the 1988 trial of Margaret Kelly Michaels, prosecutors devoted two days to exploiting a same-sex relationship in her personal history, implying that lesbianism had impelled her to force toddlers of both sexes to lick peanut butter off her cervix at the Wee Care Nursery School in Maplewood, New Jersey.

Some abuse trials may have been impacted by anti-gay propaganda swirling around seemingly unrelated issues. In February 1998, at the time of the second San Antonio Four trial, a local funding controversy was still raging.

In 1997, San Antonio talk-radio host Adam McManus and a Christian horde campaigned to end city funding of the Esperanza Center for Peace and Justice. The effort was triggered by disapproval of Esperanza’s Out at the Movies film festival, a queer film series the center had been running annually for six years. Correspondence received by the City Council stressed that Esperanza “intends to use some of the money… to indoctrinate our impressionable youth to [the gay] lifestyle.” Esperanza’s city funding was cut from $62,531 to zero.

“I love homosexuals,” declared right-wing activist Jack Finger, railing against Esperanza at a September, 1997, City Council meeting. “What I absolutely hate is the evil, wicked, child-seducing lifestyle.”

San Antonio’s gay community did not rally around Esperanza during the uproar. The left-leaning, Latina-headed resource was not a lesbigay organization per se; it represented a range of minorities. Also, relations between its director, Graciela Sanchez, and the wealthy, white gay business establishment had become strained.

Esperanza, in turn, seems to have taken little notice of the San Antonio Four. That situation finally changed in December 2010, when La Voz de Esperanza, the center’s newsletter, ran an article by Tonya Perkins defending the four women and noting the “homophobia which poisoned San Antonio in the 1990s.” At this writing, Esperanza remains the only officially gay-connected entity in Texas or beyond to call attention to the injustice. There has been no self-designated gay publication in San Antonio since 1997; the gay press elsewhere in Texas—including Dallas Voice, Houston’s OutSmart, and This Week in Texas (Twit)—has been mostly silent on the San Antonio Four.

Austin-based documentarian Deborah Esquenazi, who is making a film about the San Antonio Four, says local and national LGBTQ organizations have generally ignored her efforts to contact them. “Mostly,” she says, “they don’t respond to emails and phone calls.”

Esquenazi’s experience with Gay Inc. echoes that of others—including this writer working on behalf of Bernard Baran—who have tried to enlist the aid of such groups as the Human Rights Campaign in raising awareness of wrongfully convicted queers—or the treatment of queer prisoners, innocent or guilty. Lambda Legal, the primary LGBTQ legal resource nationally, chooses to focus on “impact litigation,” not criminal justice.

“Gay people intersect with the criminal justice system in all kinds of ways,” says New York activist Bill Dobbs, co-founder of the anti-assimilationist, pro-sex organization Sex Panic. “But when one of us gets accused of a crime, the leadership goes mute. The focus on victims has blinded us to serious injustices.”

The San Antonio Four’s predicament was mainly brought to light by people and organizations that are not gay-identified. Canadian researcher Darrell Otto discovered the case while sifting through reports on female child molesters, and became certain the women were innocent. He traveled to Texas, established a website (www.fourliveslost.com), wrote articles and blog entries on the subject, and secured the sponsorship of the National Center for Reason and Justice (NCRJ), an organization devoted to reversing wrongful convictions. Satan’s Silence co-author Debbie Nathan, then a board member of the NCRJ, helped convince the Texas Innocence Project to take the case. Articles began appearing in the Texas Monthly and elsewhere.

“At first, I thought, well, maybe those women did it,” says Deborah Esquenazi, “but once we’d sifted through the whole case, we were sure they’re innocent. My partner and I realized that could be us.”

Esquenazi and others who examined the case found the investigation flawed, the evidence meager, and the court proceedings tainted by prejudice. During jury selection, Elizabeth Ramirez’s lawyer allowed at least two individuals with moral antipathy to homosexuality to be seated as jurors—including the man elected foreman. At her sister-in-law Anna’s trial, where prosecutor Mary Delavan linked lesbianism to abuse of little girls, Rose Vasquez counted at least 75 sometimes pointedly derogatory references to lesbians. As the trial progressed, Rose and her husband signed a notarized affidavit stating they overheard a juror discussing “lesbians assaulting two children” at a restaurant with a county employee. Although the affidavit should have caused the juror’s removal, the document dropped into a void.

None of the San Antonio Four was subjected to the psychological testing and evaluation processes administered to accused sex offenders in most jurisdictions. Nowhere was it noted that Javier Limon had accused others of molesting his daughters, or that—despite his vocal distaste for lesbians—Javier had been writing love letters to Liz Ramirez, who had rejected him. His letters, which still exist, were never entered into evidence. There were also unacknowledged inconsistencies in the girls’ unevenly rehearsed testimony. At Elizabeth Ramirez’s trial, Vanessa swore her aunt had held a gun to her head while she talked with her father on the phone and told him all was well. During the trial of the other three women, Vanessa said Anna Vasquez held the gun.

As Darrell Otto notes in his blog, “[M]ost juries find child witnesses to be highly credible, in spite of the fact that it has now been shown that children often lie on the witness stand, for a variety of reasons.”

At sex abuse trials, children have been accorded privileges that sometimes trump the rights of the accused, including special seating arrangements concealing them from their alleged abusers, closed courtrooms, and testimony by CCTV or by proxy. At many of these trials, spoon-fed statements by child witnesses have comprised the prosecution’s entire case. Yet there is widespread recognition among social scientists and legal professionals that the familiar exhortation to “believe the children” can render egregious results. In Jeopardy in the Courtroom, their 1995 book on child testimony, psychologists Stephen Ceci and Maggie Bruck were among the first to show how aggressive and suggestive questioning of non-abused children can lead to “non-victimized children making false disclosures.” [P. 3.}

A recent breakthrough for the San Antonio Four was the recantation of Stephanie, Elizabeth Ramirez’s younger niece, who now says she was told she would “end up in prison or even get my ass beaten” if she didn’t recite a claim of abuse she knew to be untrue. There is now hope that even in Texas, a state where poor and working-class defendants are at a notorious disadvantage, the San Antonio Four will be exonerated as well as freed. It helps that they now have the competent legal representation they lacked at trial.

For the moment, however, the women remain in the maw of the largest—and perhaps most rigidly authoritarian—state penal system in the U.S. According to the March 23, 2012, issue of Dallas Voice, Texas leads the nation in prison rape, and “LGBT prisoners are 15 times more likely to be raped.” Amid the regimentation and the threat of violence, the women remain resistant to declarations of guilt and shows of remorse that could facilitate parole. Branded “in denial,” sex offenders who fail to cooperate with treatment may be vulnerable to one-day-to-life civil commitment.

“[One] condition of parole is to complete a sex offender program…,” wrote Anna Vasquez in 2007. “I will not take the coward’s way out to just go home.”

It takes special bravery for queers to negotiate the American criminal justice system, where homophobia seems encoded in the institutional DNA. In a study published in 2004 by The American Journal of Criminal Justice, 484 Midwestern university students were polled on attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Despite most students’ inclination to extend some rights to gay people, criminal justice majors were found to have a higher degree of anti-gay prejudice than students majoring in any other field. Homophobia among criminal justice professionals, like racism, vitiates the official charge to serve and protect everyone, without exception.

In U.S. prisons, systemic homophobia often has an evangelical dimension. Born-again Watergate felon Charles Colson’s anti-gay Prison Fellowship Ministries has been preaching to literally captive audiences nationwide since 1975. The Kansas correctional system, which matches state prisoners with “faith-based mentors,” employs many hard-line fundamentalist Christians, including members of Topeka’s Fred Phelps clan, whose website is www.godhatesfags.com. Margie Phelps, Director of Re-entry Planning for the Kansas Department of Correction, is an anti-gay firebrand whose favorite homophobic epithet is “feces eater.”

“When I went to prison,” says Bernard Baran, who survived rapes and beatings in several facilities, “I suddenly didn’t have a name. I was ‘Mo,’ short for ‘Homo.’ In the joint, gay people are at the bottom of the heap. If they think you’re a gay child molester, you’re the lowest of the low.”

Baran finally gained his freedom after unedited videos of child interviews—hidden from both the jury and his lawyer during his trial—were finally unearthed in 2004 a few months after the sudden death of Berkshire County D.A. Gerard Downing, who had claimed for years the tapes were missing. In 2006, his conviction was overturned on grounds of ineffective assistance of counsel. Baran was freed. In 2009, he won a resounding Appeals Court victory, after which all charges were dropped.

Baran spent 21 years and five months in prison. Many of those caught in the child-abuse panic fared better. As the Jordan, Minnesota, case unraveled, all defendants but one were freed. All but two of the Bakersfield defendants were released on appeal. John Stoll, among the last, was released in 2004 when four of his supposed victims, who had been pressured into telling investigators what they wanted to hear, finally recanted. The Amiraults were freed under onerous conditions enabling prosecutors to save face, but at least permitted to return home. Margaret Kelly Michaels’s conviction was overturned five years into a 47-year sentence. Others, including the allegedly child-murdering West Memphis Three, have walked out of prison in a state of near or total vindication.

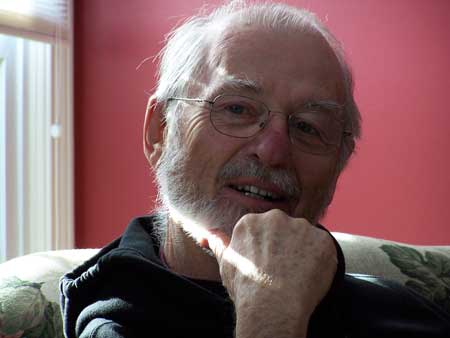

Photo credit: Terry Shanley

Others remain behind bars. Among them are some of the priests caught in the wide net of the Roman Catholic sex-abuse scandal. These include gay ex-priest Paul Shanley, 81, convicted in 2004 on the unsubstantiated “recovered memories” of a steroid addict. (Street lore falsely credits Shanley with founding and participating in NAMBLA; he did, on the other hand, found the Boston chapter of Dignity, which has disowned him.) A number of dubious, unresolved sex-abuse cases persist in Texas. Besides the San Antonio Four, there is the 1992 SRA case of Austin day-care proprietors Fran and Dan Keller, now serving 48-year sentences.

Those still in prison have, however, acquired a growing number of queer advocates. Additional rays of hope have appeared the form of queer-specific prisoner outreach efforts like Black and Pink, and events like the watershed 2010 Chicago symposium “What’s Queer About Sex Offenders? Or, Are Sex Offenders the New Queers?” Increasingly, queer activists recognize the ways in which the prison industrial complex degrades us all. There is a growing awareness that in the U.S., many people are serving time for crimes they did not commit, and that everyone trapped in the world’s most populous and retentive chain of gulags is subject to cruel and unusual punishment.

But there is a long way to go. In working exclusively on behalf of putative victims, the LGBTQ mainstream has been strengthening and refining the powers of a system that has traditionally nurtured and sheltered homophobic bias, a system that has long been the surest, sharpest means of keeping sexual minorities in line.